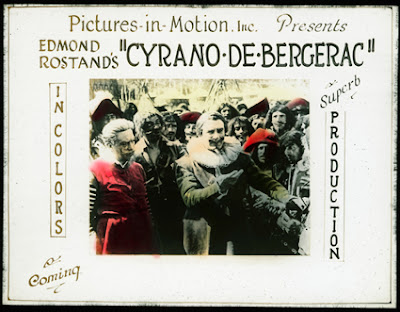

Cyrano de Bergerac in Living (Stencil) Color

March 2, 2011

One of the most interesting things to me about silent era cinema are the various technologies that were employed to bring color to the screen. Though today's audiences associate silent cinema with black and white imagery, early film goers typically enjoyed films colored by a variety of different means. The most common techniques were tinting and toning, two different processes whereby color was applied to black and white film stock by immersing individual segments in a chemical or dye bath. Sometimes this coloring would be used to indicate realistic effects, such as tinting the film blue to indicate night or coloring the frames red to indicate fire. Just as often tinting and toning was used to enhance visual interest or to enrich the image. For example it was not uncommon to color an entire film only a single color, such as yellow or orange.

More ambitious than tinting and toning, other processes were developed to color individual pictorial elements within each film frame. Even the very earliest experiments in film included color, which in these cases was painstakingly hand-appied by brush to each film frame. This time consuming and labor intensive process yielded often striking and often gorgeous results, but was only practical for shorter films.

By 1907 the length of films had increased, as well as had the number of cinemas, which exponentially increased the volume of film needing to be colored. In order to satisfy this growing demand, it became increasingly necessary to develop a larger scale solution. In addition to meeting production demands, it was also desirable to improve the quality of the color effect itself, since hand-applied colors were often applied imprecisely.

To improve the quality color application as well as to automate production, Charles Pathé developed a process which utilized a system of mechanically coloring the film emulsion by applying dye thorough a stencil (or stencils) cut from 35mm film stock. This improved process known as ‘au pochoir’ in French and ‘stencil’ in English, allowed the use of half a dozen different dyes.

Pathé patented his Pathécolor system in 1906, as “a system for the mechanical colouring of the emulsion.” The stencils, one for each color, were cut from 35mm film stock, with each frame of the stencil coinciding to a frame in the film to be colored. The stencil was hand-cut by an operator using pantograph device. While looking at an enlarged copy of the frame image, the operator would trace the objects to receive the designated colors. Then using the pantograph’s mechanical linkages, the device would reduce and replicate this tracing motion to manipulate a mechanism which would cut out the associated shape from what would become the stencil.

This operation would be repeated for every frame and every color that would be printed. After the stencil(s) were created, the film was printed by laying the stencil film strip on top of the black and white print and running it through a machine which would apply the color dye through the stencil. This process would be repeated with the corresponding stencil for every color applied.

During the early teens, stencil color gradually faded from use. Though stencil-coloured films were still being produced in the 1920s use of the technique became infrequent after 1915, during which time tinting and toning took hold as the predominant color technique.

But not entirely!

Beginning in 1922, director Augusto Genina led French-Italian co-production of Edmond Rostand's Cyrano de Bergarac. The film was colored using a combination of Pathécolor system stencil coloring and two-strip technicolor and is credited with being the first full color feature film. Released in 1925, the two-hour film took three years to produce though it is difficult to ascertain how much of the time was devoted to film production and how much was devoted to creating the color prints.

What is clear is that color was a major selling point in the American slide promoting the film. Perhaps color was also emphasized as because the film featured French and Italian actors unfamiliar to American audiences.

What ever the case, it's hard to argue with the result...