Chaplin at (and after) Keystone

February 22, 2011

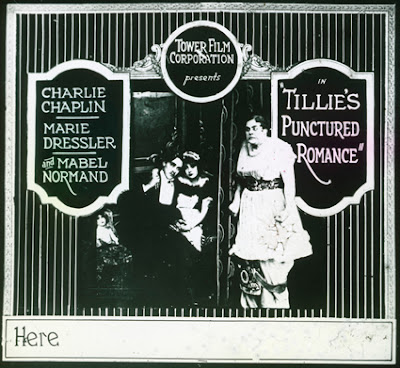

Charles Chaplin began his film career at Mack Sennett’s Keystone Film Company in 1914, debuting in Making a Living (February 2, 1914). He appeared in 36 films during his year at Keystone before defecting to the Essanay Film Company in early 1915. With the exception of the six-reel Tillie's Punctured Romance (December 21, 1914) Chaplin's Keystone output consisted primarily of short one-reel comedies (25), with a handful of two-reelers (7) and short split-reel shorts (3) as well.

Since the practice of using lantern slides to advertise motion pictures began in the US in 1912 (according to the earliest evidence I have found), it seems reasonable to ask whether Keystone used slide advertising to capitalize on the skyrocketing popularity of their new star. Based on all evidence I have found to date, the answer appears to be "no." I base this conclusion first on the fact I have never seen an example of an original Chaplin Keystone slide, but more empirically on all available evidence that Keystone didn't begin using slide advertising until late 1915. The earliest Keystone slides I have discovered thus far advertise comedies released in November and December 1915 - seven months after Chaplin's departure for greener pastures.

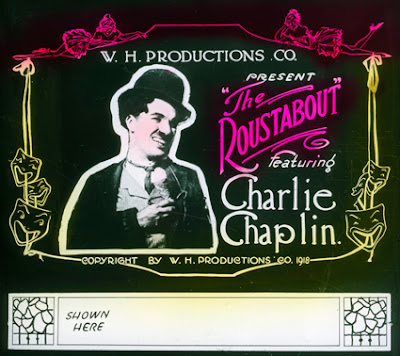

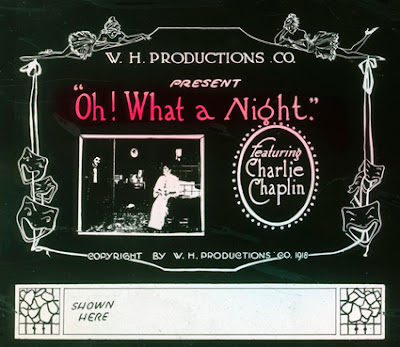

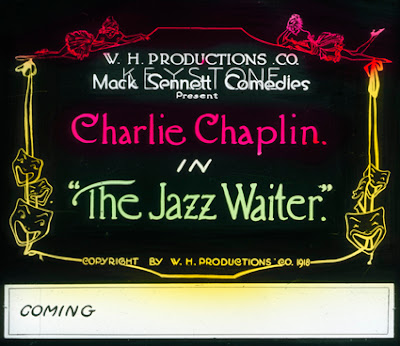

It is well known that prints of Chaplin's early comedies continued to circulate for decades after his departure from Keystone. Battered bootleg prints continually found their way to the screen, but legitimate re-issued copies also circulated. The four Chaplin "Keystone" slides featured today are the product of one of these legitimate re-issuing distributors. The slides feature a 1918 re-issue of Tillie's Punctured Romance as well as three retitled Chapin Keystone shorts which were possibly (probably?) pawned off on the public as "new" Chaplin releases.

Ted Okdua and David Maska's fascinating volume Charlie Chaplin at Keystone and Essanay: Dawn of the Tramp provides interesting insight into the background of these 1918 re-issues:

"The Mutual Film Corporation, through an arrangement with the New York Motion Picture Company, originally distributed most of the early Keystone Comedies. [...] In 1915, the New York Motion Picture Company was sold to the Triangle Film Corporation, formed by D.W. Griffith, Thomas Ince, and Mack Sennett. Sennett continued to produce films, which were now released as Triangle-Keystone Comedies. Sennett left Triangle in 1917, and prior to the company's collapse the following year, Harry Aitken, one of its founders, reissued a number of Keystone films, including several Chaplins.

Several film production companies were shut down during the influenza epidemic of 1918, resulting in a shortage of marketable product, especially where comedies were concerned. Seizing the opportunity, newly-formed "states' rights" companies [...] began issuing re-edited versions of Keystone comedies. Two such outfits were Tower Film Corporation and Jans Producing Corporation.

Also in 1918, W.H. ("Wonderful Hits") Productions, another states' rights distributor, re-edited 750 Keystone comedies and reissued them under new titles, including several Chaplin shorts. It wasn't widely known at the time that Harry Aitken and his brother Roy owned both W.H. Productions and Tower Film Corporation. Rival distributors complained to the Federal Trade Commission that these old movies were being passed off as new product, so W.H. Productions agreed to call attention to the fact that they were re-releases. Hence, the title credits for W.H. reissues would read "Charlie Chaplin in The Good-for-Noting, Former Title His New Profession" and so forth. The opening titles for W.H. reissues also carried 1918 copyright notices, although many of the films had never been copyrighted to begin with. This was just a ruse on the part of W.H. to deter other distributors from bootlegging its own releases."

Ironically, the fact of these re-issues are one reason why the Chaplin's Keystones still exist today. According to Okdua and Mazaka, "Many Keystone comedies survive today thanks to W.H. Productions. Unlike the the products of major studios which were rented to movie theaters and then returned to the studio's vaults, the films of W.H. productions were sold outright to regional distributors for $80 a reel. Thus the W.H. Keystones "escaped" from the owner's control and passed from hand to hand as time went on."

It seems apparent that slide advertisements were never produced for the Chaplin's original Keystone output, but just as the re-issuers may inadvertently saved the Keystone films, so too are they to thank for leaving behind these 3x4" glass remnants of their promotion.