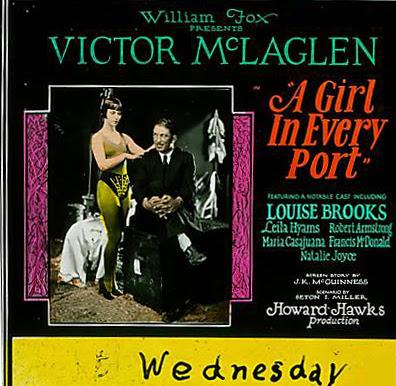

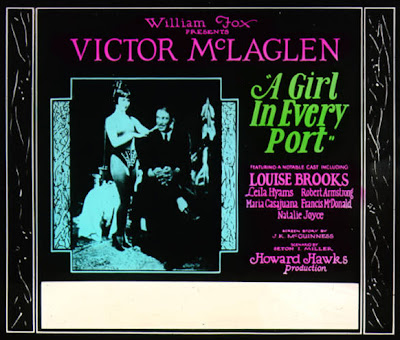

A Girl In Every Port

January 1, 2011

What better way to kick off the new year than with another meticulously researched article by our good friend Thomas Gladysz? Thomas was the very first STARTS THURSDAY! guest contributor with his article last August highlighting Louise Brooks' in American Venus (1926). Today Thomas continues exploring Brooksie's filmography with Howard Hawks' A Girl In Every Port (1928).

Throughout the month of January, the British Film Institute is celebrating the work of the American director Howard Hawks (1896 – 1977). Hawks is best known for the movies he made during the sound era. His films include such classics as Dawn Patrol (1930), Scarface (1932), Bringing Up Baby (1938), Only Angels Have Wings (1939), His Girl Friday (1940), Sergeant York (1941), To Have and Have Not (1944), The Big Sleep (1946), Red River (1948), Gentlemen Prefer Blondes (1953), and Rio Bravo (1959). Though a remarkable body of work, one could mention still more notable films by Hawks, including A Girl in Every Port (1928). It’s considered the best of the director’s eight silent films.

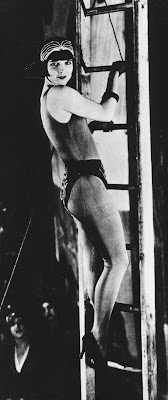

A Girl in Every Port is a “buddy film,” and it includes a romantic triangle – a reoccurring motif in many later works by the acclaimed director. The film tells the story of two sailors (played by Victor McLaglen and Robert Armstrong) and their adventures with various women in various ports of call around the world. Louise Brooks plays Marie (Mam’selle Godiva), a high diver and sideshow siren and the love interest of each sailor.

Released by Fox, A Girl in Every Port premiered on February 18, 1928 at the Roxy Theater in New York City. The film received good reviews and played to a packed house. Trade ads placed by Fox claimed the film set a “New House Record – and a World Record – with Daily Receipts on February 22 of $29,463.” Considering ticket prices of the time, that’s a lot of money to take in on a single day.

The film made an even bigger splash in France. Writing in his “Paris Cinema Chatter” column in the New York Times in 1930, Morris Gilbert noted “. . . there are a number of others – mostly American – which have their place as ‘classics’ in the opinion of the French. . . . They love A Girl in Every Port, which has the added distinction of being practically the only American film which keeps its own English title here.” The film enjoyed an extended run in the French capitol, and would linger for decades in the French consciousness.

Writing in Cahiers du Cinéma in 1963, the French film archivist Henri Langlois stated, “It seems that A Girl in Every Port was the revelation of the Hawks season at the Museum of Modern Art in New York. For New York audiences of 1962, Louise Brooks suddenly acquired that ‘Face of the century’ aura she had had, many years ago, for spectators at the Cinema des Ursulines. . . . That is why Blaise Cendrars confided a few years ago that he thought A Girl in Every Port definitely marked the first appearance of contemporary cinema. To the Paris of 1928, which was rejecting expressionism, A Girl in Every Port was a film conceived in the present, achieving an identity of its own by repudiating the past.” (from The Modernity of Howard Hawks)

Significantly, Brooks stands as what might be the first “Hawksian woman.” The BFI website additionally notes, "History ranks this as the most significant of Hawks' silent films, because it seemingly persuaded G.W. Pabst to ask for Louise Brooks in Pandora's Box.”

But did it?

The oft repeated claim** that Pabst chose Brooks to play Lulu after having seen her in A Girl in Every Port is open to debate. If one were to look at a chronological list of the actresses’ films, the assumption seems to make sense. As mentioned earlier, the Hawks' film (in which Brooks plays a distant temptress not unlike Lulu) premiered in the United States in February, 1928. In Germany, Pabst was attempting to cast Lulu just months later in the Spring and early Summer of the same year.

However, as Berlin newspaper reviews show, Blaue jungens, blonde Madchen (the German title for A Girl in Every Port) was not shown in the German capitol until December of 1928, after production on Pandora's Box was completed. Could Pabst have seen the Hawks' film prior to its release in Germany? Could he have seen an advance screening?

Or, might Pabst have noticed Brooks in one of her earlier films, such as Die Braut am Scheidewege (Just Another Blonde) or Ein Frack Ein Claque Ein Madel (Evening Clothes) - each of which were shown in Berlin and received significant coverage prior to the production of Pandora’s Box?

Whatever the answer, A Girl in Every Port remains an entertaining film worthy of greater recognition – not only because it stars “pert” Louise Brooks, but because it prefigures the great films Hawks made in coming years.

The reviewer for the English Kinematograph Weekly sensed as much in March, 1928 when they wrote, “Louise Brooks made a charmingly heartless vamp. . . . It has the novelty of a love interest that does not materialize, which is replaced by the friendship between two men.”

A Girl in Every Port will screen at the British Film Institute on January 2 and January 7, 2011.

** The claim that Pabst chose Brooks after having seen her in A Girl in Every Port was likely first made by James Card in his 1956 article "Out of Pandora’s Box: Louise Brooks on G. W. Pabst." And, it was repeated by Brooks herself in filmed interviews in the 1970's.

--- THOMAS GLADYSZ

Thomas Gladysz is an arts journalist and author. Recently, he wrote the introduction to a new “Louise Brooks edition” of Margarete Böhme's classic book, The Diary of a Lost Girl (PandorasBox Press). Gladysz will speak about his new book at the Village Voice Bookshop in Paris on January 13, followed by a screening of the film at the nearby Action Cinema.

Gladysz lives in San Francisco and is currently working on a new book about Louise Brooks. He is also maintains the Louise Brooks Society website at www.pandorasbox.com